Practical Formal Verification for Distributed Systems

Introduction

In a rapidly evolving tech landscape where cloud systems scale exponentially and AI-assisted programming takes center stage [1], mastering the art of balancing outage costs with preventive measures is more critical than ever. This pressing need has invigorated the exploration of formal methods, a domain that includes both model checking, exemplified by tools like TLA+ [2], and formal verification techniques.

While model checking has found its way into practical engineering workflows [3], formal verification remains a largely untapped resource for ensuring the reliability of cloud-scale distributed systems.

In this article, we advocate for a pragmatic approach to formal verification, emphasizing its value as a complement to model checking. Our thesis is straightforward: as AI-assisted programming becomes ubiquitous, the ability to rigorously reason about system correctness will be a key differentiator. Practical formal verification, we argue, could be the missing piece that takes the robustness of cloud-scale distributed systems to the next level.

Outage: cost vs. prevention

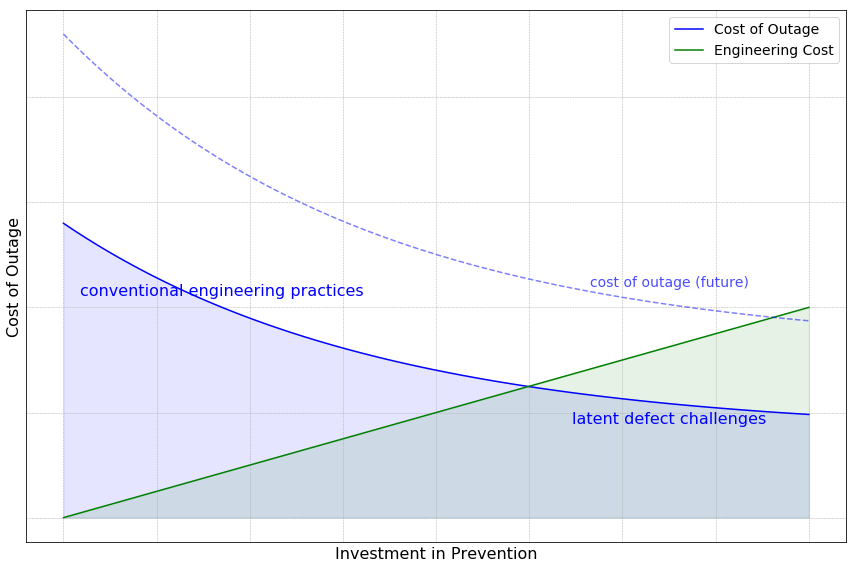

The above graph illustrates the relationship between the cost of outages and the preventive measures taken beforehand. On the x-axis, we have the preventive investments, and on the y-axis, we see the resulting cost when outages cannot be fully prevented.

The blue curve showcases the cost of outages as the product of software defects and their probability. This cost diminishes as preventative investment rises. The upper section of this curve highlights the benefits of conventional engineering practices, such as unit testing, integration testing, and strategic release stages. In this zone, the majority of straightforward software defects are rectified. Moreover, these practices diminish the likelihood of more obscure defects, leading to a steep decline in outage costs with increased investment.

However, as we move towards the bottom section of the curve, the scenario becomes more challenging. Here, latent defects, often deeply embedded in the software stack, remain hidden until significant scaling takes place. These defects, though rare, can have a profound impact. To counter them, a substantial investment is necessary, but the returns (in terms of outage cost reduction) are lesser in comparison to the initial phase. Yet, when weighing the potential damage from these defects against the preventative investment, the decision is clear: it’s prudent to keep investing until an equilibrium is reached.

Compounding this scenario, the blue curve is set to rise with the scaling of cloud systems. Even with a conservative annual growth rate of 20%, the cost of outages will double within four years. In contrast, the green curve, representing engineering costs, increases linearly over time. This discrepancy means that the challenges represented by the bottom section of the blue curve will grow exponentially, making investment in this area increasingly valuable.

Landscape of formal methods

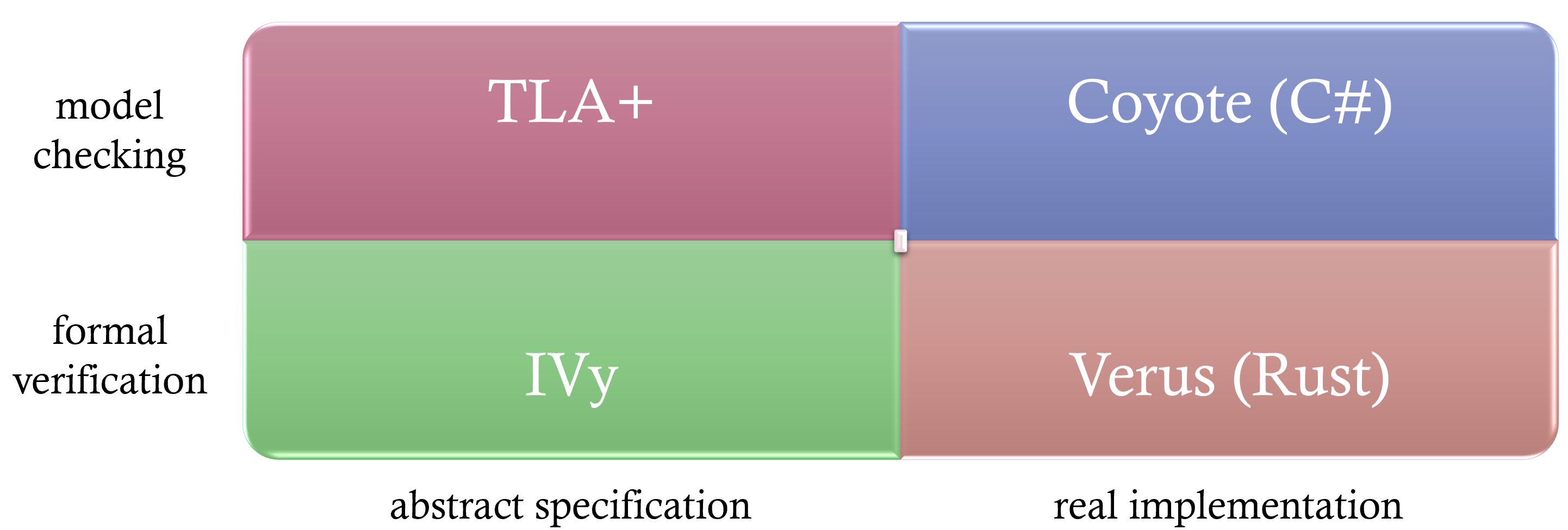

Formal methods can be visualized across four quadrants in a two-dimensional space, categorized by their approach and applicability. The Y-axis differentiates between model checking and formal verification, while the X-axis distinguishes between techniques applied to abstract specifications versus real implementations. Let’s delve into each quadrant:

- Model checking on real implementation (top-right quadrant):

Example: Take Coyote [4], originally developed at Microsoft Research and now open-sourced. In traditional testing, executing a test case 100 times yields roughly identical results each time. With Coyote, each execution explores different task interleavings, thanks to its control over asynchronous task scheduling. As a result, invariant violations surface more quickly, and when detected, Coyote captures a trace, allowing for deterministic replay and debugging.

- Model checking on abstract specification (top-left quadrant):

Example: Consider TLA+ [2], a specification language. Real-world systems contain myriad details, many of which are non-essential to verifying correctness. By abstracting core logic and eliminating extraneous details, specifications in TLA+ focus solely on crucial behaviors. Model checking these specifications explores all defined interleavings, capturing and replaying traces whenever an invariant is violated.

- Formal verification on abstract specification (bottom-feft quadrant):

Example: Instead of verifying through exhaustive exploration, formal verification offers mathematical proof of correctness. For instance, using the IVy language [5], one can abstract essential distributed system logic, write specifications, and then mathematically prove their correctness using the IVy toolchain.

- Formal verification on real implementation (bottom-right quadrant):

Example: Verus [6] is a pioneering open-source project marrying formal verification with real-world implementation in the Rust language. It exemplifies the potential of integrating rigorous mathematical proofs with tangible, working code.

Formal verification: a practical perspective

Diving into the realm of formal verification, it’s essential to distinguish between “practical” formal verification and its academic sibling. While both aim for the same overarching goal—ensuring system correctness — their approaches and concerns differ markedly.

From an engineering standpoint, formal verification fills certain voids that model checking doesn’t address. Model checking’s primary challenge lies in the definition of safety properties or invariants. Engineers can usually spell out ultimate safety properties for distributed systems with ease: “ensure no data loss in a storage system” or “a consensus protocol must converge to a single value.” Yet, the intricacies arise due to the global nature of these invariants. To verify them, collaboration among multiple distributed entities becomes indispensable. For instance, confirming no data loss requires consulting all storage nodes, while verifying a consensus protocol demands interrogation of numerous nodes. These global checks are cumbersome in runtime, pushing developers towards local, intermediate invariants that individual nodes can easily enforce. But this approach isn’t without its pitfalls: How many intermediate invariants are enough? Are they comprehensive in ensuring the overarching safety goals?

Enter formal verification. It necessitates the formulation of inductive invariants which, collectively, can vouch for a protocol’s correctness. Interestingly, these inductives often pertain to individual nodes, making their runtime enforcement more feasible.

However, there’s a nuance to appreciate. In practical engineering, the aim of formal verification isn’t just about achieving system correctness. While academics may laud formal verification for its prowess in managing unbounded state spaces, on the ground, this advantage doesn’t always translate to practical superiority. Even bounded model checking often suffices to ensure system correctness. Whether scrutinizing data safety across a set number of nodes or checking a consensus protocol with limited participants, it’s unlikely for a system to work in a restricted setting but fail when scaled. The true value of formal verification lies in its methodical approach — systematically proving correctness, leading us to pinpoint essential inductive invariants. Once identified and transformed into runtime checks, these invariants become the vigilant guardians of system reliability.

To distill our perspective on practical formal verification: It’s about pinpointing the comprehensive set of inductive invariants that vouch for a system’s safety. We’re content with bounded settings, like consensus among a specific number of nodes or ensuring linearizability within a set operation count. By doing so, we often streamline our specifications, even if it means forgoing generalization — a primary concern in academic formal verification.

IVy

This is where IVy [5] comes in. IVy offers both a language for specifying distributed protocols and a toolkit for formal verification. For those who have worked with TLA+, transitioning to IVy is relatively straightforward.

Using IVy is an interactive experience. It starts with specifying a distributed protocol. With a target safety property, you ask IVy to verify it. Since most safety properties aren’t automatically inductive invariants, IVy often rejects the proof and provides counterexamples. These show scenarios where a legitimate state leads to a violation of the safety property after a valid action. This feedback helps users recognize missing base invariants.

The process is iterative: you add these base invariants, and IVy checks them. If IVy still flags issues, its feedback points to the need for more complex inductive invariants. As users propose these invariants, IVy confirms their validity or provides counterexamples. The cycle continues until IVy can’t find any more counterexamples, indicating that the safety property has been proven.

From an engineering viewpoint, this iterative method is useful. Each cycle deepens our understanding of the distributed protocol. Moreover, many of the identified inductive invariants are local, making them easy to implement as runtime checks. By adding these checks to the real system, we transition the correctness assurance from the specification to the actual implementation.

Why not Dafny?

Dafny [7] has garnered attention as a tool for the formal verification of distributed protocols. However, based on our experiences, Dafny falls short in serving the specific needs of practical formal verification. A key limitation lies in Dafny’s inability to consistently generate concise and easily understandable counterexamples, a crucial aspect in the journey of identifying inductive invariants.

Toy consensus example

To grasp the concept of inductive invariants and their discovery, let’s walk through a simplified consensus protocol.

Protocol overview

- We have three nodes:

n_1,n_2, andn_3. - We have two values:

v_1andv_2. - Nodes can cast a vote for any value, provided they haven’t voted already.

- Consensus (or a value being decided) is achieved when 2 out of the 3 nodes vote for the same value.

Safety property The protocol must ensure that only one value is decided upon. In other words, two different values can’t both achieve consensus.

Take a moment to consider this setup. A node, if it hasn’t previously voted, can vote for any value. Once a value receives votes from two nodes, that value is deemed “decided”. The core safety aspect we’re ensuring is that only one value reaches this “decided” status.

IVy specification

- Apart from nodes and values, our specification includes two quorums,

q_1andq_2. The axiomsquorum_q1andquorum_q2provide the simplest possible definitions for these quorums (e.g.,q_1consists of two nodesn_1andn_2), which we’ll elaborate on later. - We employ several relations, which are boolean-returning functions. For those versed in Prolog, these relations should feel familiar. Capitalized variables act as wildcards, matching any instance, whereas lowercase ones pinpoint specific instances. For instance,

vote(N, V)indicates voting status for any node-value pairing, whilevote(n, v)refers to a specific node-value combination. - The initial state,

vote(N, V) := false, signifies that no node has voted. Conversely, the statementvote(n, v) := truein thecase_voteaction indicates a chosen node (denoted asn) voting for a specific value (v). - The protocol delineates two actions:

case_vote: Here, a nodencan vote if it hasn’t voted before, as represented by the~vote(n, V)precondition (notice the capitalized V includes all values).decide: This action is triggered when a quorum of nodes have voted for the same valuev.

type node = {n1, n2, n3}

type value = {v1, v2}

type quorum = {q1, q2}

relation member(N:node, Q:quorum)

axiom [quorum_q1] member(n1, q1) & member(n2, q1) & ~member(n3, q1)

axiom [quorum_q2] member(n1, q2) & ~member(n2, q2) & member(n3, q2)

relation vote(N:node, V:value)

relation decision(V:value)

action cast_vote(n:node, v:value) = {

require ~vote(n, V);

vote(n, v) := true

}

action decide(q:quorum, v:value) = {

require member(N, q) -> vote(N, v);

decision(v) := true

}

after init {

vote(N, V) := false;

decision(V) := false;

}

export cast_vote

export decide

Interactive invariant discovery

Diving into the discovery of inductive invariants, let’s start by stating our primary safety invariant: only a single value can be decided upon. In essence, any two decided values must be identical.

invariant decision(V1) & decision(V2) -> V1 = V2

IVy flags this invariant as non-inductive. The counterexample it provides begins with a state where decision(v2) = true and decision(v1) = false, with both vote(n1, v1) and vote(n2, v1) being true. This state is valid as it adheres to our invariant. However, executing the decide action would result in decision(v1) = true, violating the invariant since both v1 and v2 have now been decided.

This is a pivotal moment in understanding inductive invariants. One might argue that the state of decision(v2) = true and both votes for v1 isn’t a realistic scenario. This is true, but the essence of inductive invariants lies in the fact that the reachability of the beginning state is irrelevant. As long as it fits the invariant, it’s deemed valid. This counterexample, albeit adversarial, showcases IVy’s robustness.

From this counterexample, it’s clear we must prevent decision(v2) = true when two nodes have voted for v1. To fortify our proof, we add an intermediate invariant ensuring that a decided value has the backing of a quorum:

invariant decision(V) -> exists Q:quorum. forall N:node. member(N, Q) -> vote(N, V)

Yet, IVy rejects the proof again. The new counterexample retains the original state but adds both vote(n1, v2) = true and vote(n2, v2) = true because of the added invariant.

It’s evident that having both vote(n1, v1) and vote(n1, v2) as true is problematic, indicating a node has voted twice. So, we introduce another invariant, which states all the values voted by an arbitrary node must be be identical.

invariant vote(N, V1) & vote(N, V2) -> V1 = V2

With this addition, IVy accepts the invariants, collectively making them inductive. This confirms the safety of our target invariant under the given specification — no two values can simultaneously be decided. Crucially, the final invariant is local, pivotal for correctness, and can be continuously validated during runtime. We can envision each node maintaining a tally of its votes, with any node exceeding one vote indicating a potential breach of the invariant. This methodology extends to more intricate protocols, like Paxos, where individual nodes can also monitor local conditions to ensure system safety.

Simplification via specificity

One of the key hallmarks of “practical” formal verification lies in the art of simplification. Let’s delve into how this is highlighted in our toy concensus specification.

Firstly, we limit the scope to just 3 nodes and 2 values. This might seem restrictive, but it aligns perfectly with our primary objective: the discovery of all inductive invariants. Smaller specifications not only speed up the verification process but also yield counterexamples that are easier to interpret.

Secondly, we use specific axioms to define our quorums. Instead of adopting a generic representation that demands overlapping nodes between any two quorums, we go for a more straightforward approach. This simplification doesn’t compromise our ability to identify all the required inductive invariants.

However, it’s worth noting that these simplifications come with their trade-offs. For example, if we decide to extend the system to handle more nodes and values, we’ll need to manually update the specification. This is generally a one-time effort to avoid unexpected surprises.

Also, keep in mind that extending the specification can significantly increase the time required for verification. For instance, in a specification modeling the Paxos concensus protocol, when expanding the sets of Ballot IDs and values, the verification time shot up exponentially. To illustrate, allowing ballots to choose between 0 and 7, and values from a set of 3, took nearly 3 hours for verification. While it’s possible to craft a more complex specification that verifies faster, it contradicts our aim in practical formal verification: simplicity is key, as long as it enables us to identify all inductive invariants.

| Ballot ID | Value | Verification Time |

|---|---|---|

| 0, 1, 2, 3 | {v1, v2} | 4.5s |

| 0, 1, 2, 3 | {v1, v2, v3} | 5.9s |

| 0, 1, …, 7 | {v1, v2} | 6m27s |

| 0, 1, …, 7 | {v1, v2, v3} | 171m26s |

Conclusion

In an imminent future, where AI-assisted programming takes center stage [1], the capability to reason and ascertain high-level system correctness will stand out as a pivotal differentiating skill. For those of us crafting the foundational layers of cloud-scale distributed infrastructure, it’s imperative to not only familiarize ourselves with tools like TLA+ but to also become adept at practical formal verification. It isn’t just about knowing the tools — it’s about seamlessly integrating them into our everyday workflow, ensuring that the systems we build are robust and fail-proof.